Physical fitness and physical activity

Last week I told you that I would be describing all the long-term conditions of later life which impede our mobility, agility, well being and independence. We know that these, the non-communicable diseases (NCDs), can be both prevented and treated by exercise. The studies which show this depend on comparing physical activity and physical fitness with disease risk and the outcome of treatments.

Before tackling the NCDs it might be helpful to consider the differences between physical activity (PA) and physical fitness, also known as aerobic fitness or cardio-respiratory fitness (CRF). It is tempting to believe that there is a simple relationship between these measures but unfortunately there is not.

What is CRF?

There are a number of aspects of physical fitness including agility, balance, coordination, flexibility, muscular strength, and physical fitness. It is physical fitness which interests me and which has the strongest association with health – and that is what I shall be considering. And when I talk about physical fitness I am referring to CRF..

CRF is a measure of the greatest sustainable effort of which we are capable and is best measured by the fastest rate at which we can absorb and use oxygen – a critical fuel for sustained exertion. This is known as maximum oxygen uptake. Oxygen uptake is abbreviated as VO2 and maximum oxygen uptake as VO2max. For those without musculoskeletal disorders VO2max can only be attained by using our most powerful muscles – the leg muscles.

VO2max is therefore determined by measuring oxygen uptake during maximal leg exercise – either on a treadmill or an exercise bicycle. Because the oxygen uptake during both walk/running and cycling is predictable, the VO2 during exercise and the VO2max are usually “predicted” rather than being measured directly. Direct measurement requires complicated machinery and qualified staff and is is too expensive and cumbersome for routine use..

The main determinants of CRF are age, inherited characteristics, gender, body weight and habitual physical activity.

And what is physical activity

Physical activity (PA) is much more difficult to pin down and measure than CRF. It is all to do with movement – how often, how hard and for how long. It can be measured either by asking the individual how much they do or by measuring activity with an “accelerometer” which is a sophisticated pedometer. Asking the individual is done by standardised questionnaires but the results are extremely unreliable. People appear to believe that they do a great more than they really do, overestimating by a factor of 50 to 100%. Accelerometers are much more accurate but still leave a lot to be desired.They cannot measure all daily activities with any precision but they certainly capture the totality of daily activity far more reliably than the unreliable witness of the individual filling in a questionnaire.

The relationship between PA and CRF

Broadly speaking, the more exercise you take the fitter you become. However the vast variety of possible activities makes it extremely difficult to work out the relationship much more accurately than that. There are also some inbuilt factors which decide CRF which are independent of exercise habit. These include:

- Inherited characteristics. Everyone is born with different potential fitness levels. There are those whose CRF without any training at all is higher than others who have undertaken strenuous exercise regimes.

- Gender. Females have approximately 20% lower CRF levels than males, due to their different, hormonally determined, muscle and fat distribution.

- Age. After the mid twenties our CRF gradually falls off by between a half and two percent per year, depending on habitual exercise habit. The more we exercise the slower the decline. This is made more complicated by the fact that the older we are the less we exercise. When measuring the CRF of large numbers of individuals the differences can be enormous and it is habitual exercise which has a greater influence than age.

- Body weight. The heavier you are the harder you have to work to move about. Habitual exercise habit does affect BMI and there a few people who are both obese and physically fit but they are few and far between – perhaps about 5% of obese people have a high CRF.

- Unresponsiveness to training. There are few people for whom physical training seems not to increase CRF. My suspicion is that this is pretty uncommon.

Why does it matter

For the vast majority, regular exercise increases physical fitness or CRF. If a sedentary person takes up a fitness regime the increase in CRF over say six months is about 30% – but it can be greater for the really unfit.

The assessment of the value of exercise in preventing or treating disease is made from a comparison between those with high or low physical activity levels and high or low CRF levels. Some of the outcomes measured include incidence of the disease being studied, mortality, recovery rates, complications and disability scores. In nearly all instances CRF comfortable beats physical activity (PA) as a predictor. When PA is measured with an accelerometer the difference is less.

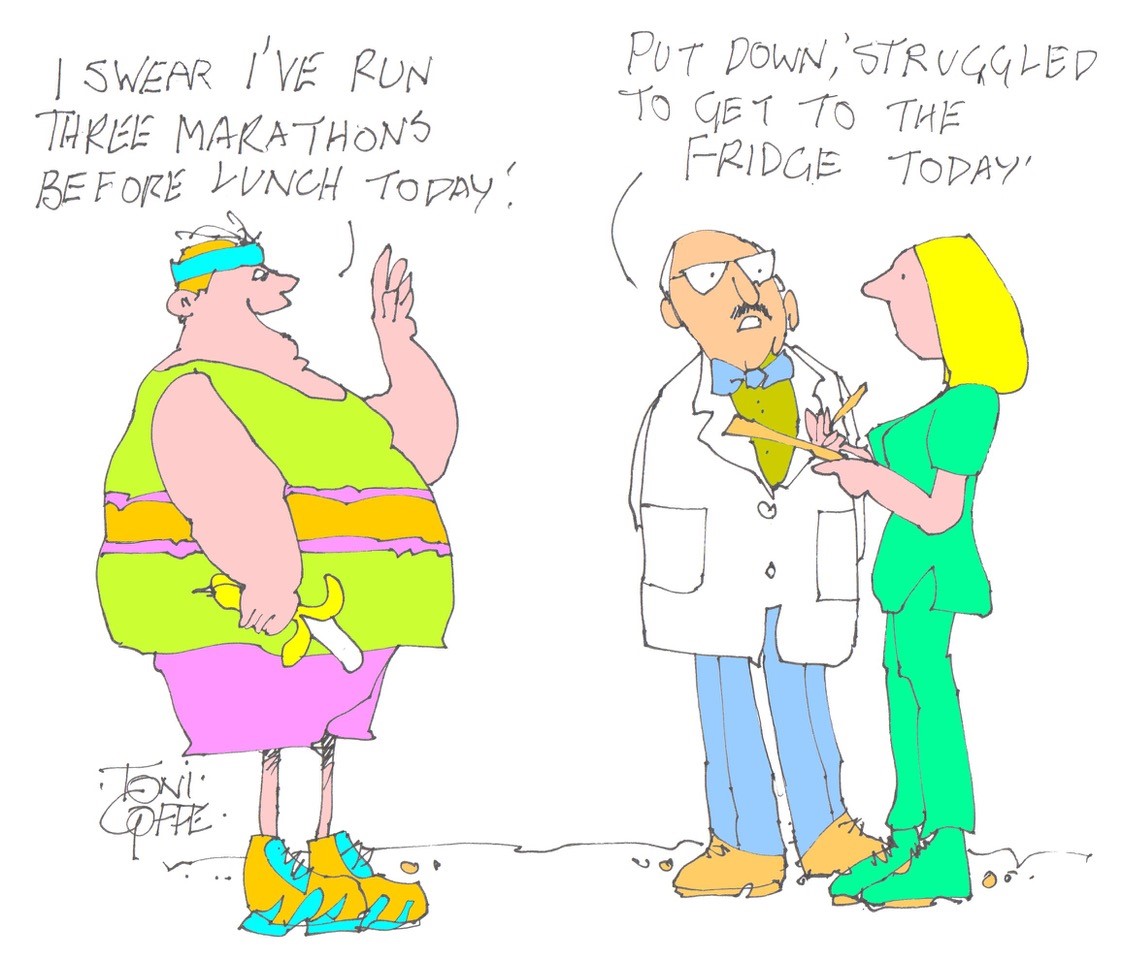

Why the difference – well it may be inherited characteristics (perhaps those born with low CRF potential are also more prone to heart disease) or it may be due to the unreliability of the assessment of PA. I believe that it is the latter and this is strongly driven by social desirability bias, the need to seem more “virtuous” than we are!

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Pregnancy

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking