PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND LIFE EXPECTANCY

The relationship between how much you do and how long you live is important for all of us. More light has been thrown on this subject by a paper just published in the British Medical Journal. The authors analysed a number of studies with a total of more than 36,000 subjects followed for about 6 years, with 2149 deaths. Average age was 63 years. 73% were women. All subjects had their physical activity measured by an accelerometer (a pedometer-like device which measures total activity) and were divided into four groups according to total activity. I suggested in my last blog that measuring actual movement with such devices is the most reliable way of assessing activity levels, followed by measuring physical fitness (much more about this in future blogs), with responses to physical activity questionnaires a distant third. This study is, therefore, based on the most reliable data.

More activity = lower risk

The risk of death was taken as 1 for the least active group. With levels of increasing activity the risks of dying fell to 0.48, 0.34 and 0.27. That means that the most active group had one quarter the risk of dying of the most active group. There was a similar but less marked gradient in mortality when levels of light physical activity and of moderate to heavy activity were compared. The conclusions were that any level of activity is life-saving and that the more exercise the better, with some flattening off of the benefit with increasing levels of exercise.

Sitting a lot is bad

The study also looked at the risks of sitting about. The risk of dying increased steadily from the most sedentary to the least sedentary with a risk of dying of 2.6 times for the most sedentary compared to the least sedentary (see previous Blog “Sedentary Activity”).

Is there a threshold?

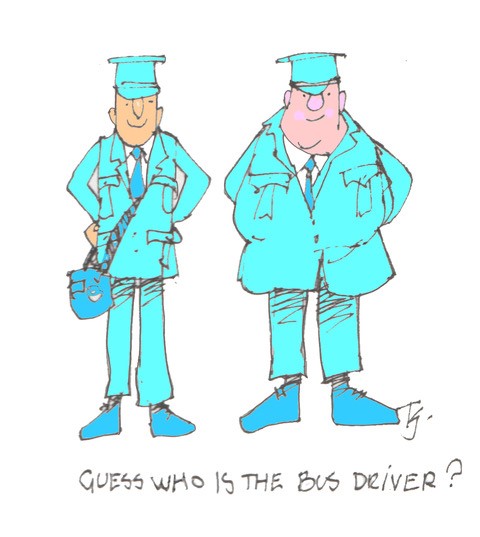

In the 1950s, Professor Jerry Morris’s looked at the fates of London bus drivers compared with conductors. The model of the driver was sitting behind the wheel, unable to exercise and fuming at all those pesky motorists and taxi drivers. The conductors on the other hand were on their feet all day, skipping up and down the stairs and taking plenty of exercise. Sure enough the drivers had a significantly higher mortality, largely due to a greater risk of coronary disease.

In those days the number of physically active workers was considerably greater than is the case nowadays – mechanisation has greatly reduced the role of occupation in making the working man take exercise. Morris repeated his findings in a comparison of the leisure time activities of civil servants. Those who exercised vigorously as part of their leisure activity fared much better than their sedentary colleagues. One of the findings was the presence of a threshold for the effect of exercise – it was only those taking vigorous exercise in their leisure time who benefitted. Lower levels of exercise did not seem to prolong life.

Even a little exercise is good

This much larger overview of a number of studies, with measurement of exercise dose, has modified this view – even small amounts of physical activity reduce mortality and the greatest proportional benefit is seen with small increases in exercise. However if you want to maximise your lifespan (and healthspan) you do need to take as much exercise as possible – and don’t sit about!

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Pregnancy

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking