Peripheral Vascular Disease

‘Used to be rock around the clock, now it’s limp about the block.’ Anon.

Peripheral vascular disease

Atheroma (‘hardening of the arteries’) can involve any part of the vascular tree. Arterial disease of the legs is called peripheral vascular disease (PVD). The main risk factors are the same as for other forms of atheroma such as coronary heart disease. These include diabetes, cigarette-smoking, high blood pressure and dyslipidaemia. In a minority there is a strong inherited predisposition. The combination of cigarette smoking and diabetes is particularly dangerous.

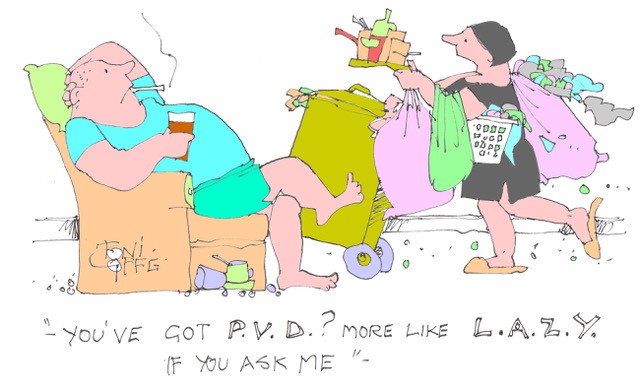

PVD affects about 10 per cent of diabetics at 10 years after diagnosis, rising to 45 per cent at 20 years. The incidence in non-diabetics is between 5 and 10 per cent for over 65-year-olds. Like coronary disease, PVD initially causes muscle pain on exertion – usually pain in the calf when walking, resolving rapidly on stopping. Just like angina, but in the leg muscles instead of the heart muscle. This is called intermittent claudication, or intermittent limping, named after the emperor Claudius, a famous limper. Progression of the arterial narrowing may lead to blockage and severe lack of blood to the feet. The lower parts of the legs may develop ulcers which won’t heal. Toes become painful, then white and ultimately black and gangrenous, requiring amputation. If you are diabetic, please don’t smoke.

Penile blood supply may also be affected by PVD, causing erectile dysfunction. Erections are absent, weak or cannot be sustained – a cause of much distress and frustration to those so afflicted.

Exercise in the prevention of PVD

Regular exercise improves arterial elasticity and lessens arterial stiffness. This was well illustrated by a study of middle-aged first-time marathon runners. By the end of their training the improvement in the state of their arteries was enough to make them appear four years younger.

PVD is closely linked to other forms of arterial disease. About 60 per cent of PVD sufferers have concurrent coronary artery disease and 30 per cent have cerebrovascular disease. Preventative measures for all these diseases are very similar. Regular exercise and high levels of physical fitness reduce three out of the four most important risk factors for PVD – that is to say, diabetes, high blood pressure and abnormal blood lipids. As a result regular exercisers rarely suffer from PVD.

Exercise in the treatment of PVD

There are operations to restore blood supply – either bypass grafting or angioplasty (as for coronary artery disease but easier because you don’t need to stop the heart) – but these are needed only when symptoms are severe or when the limb is threatened. The only other effective treatment is exercise, particularly walking. The best results are obtained when the sufferer walks to the greatest degree of calf pain tolerable for more than 30 minutes on three or more days per week. The Cochrane Review of this treatment covered 1,837 adults in 32 trials. The treated groups showed significant increases in both pain-free walking distance and maximum walking distance.

The way in which walking improves intermittent claudication is probably by provoking muscle ischaemia (inadequate blood supply), which encourages the growth of new small blood vessels (collaterals) to bypass the narrowed or occluded arteries. Structural changes in the walking muscles also contribute to the improvement.

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking

Another interesting article Hugh. About four months after recovering from unstable angina and the installation of another stent I suddenly became aware of a literal ‘pain in the backside (right cheek)’ after walking distances of about 100 meters that eased quickly when I rested, just like angina but in the bum muscle. After seven years and several sessions of physiotherapy, a vascular referral, medication and advice to exercise regularly to max pain tolerance, there was no change. Having stopped the medication and two months into a low-carb lifestyle (for other reasons) the pain simply vanished as did my erectile dysfunction which I had endured for much longer. What is going on here? I have noticed that ‘exercise to max pain tolerance’ is not given to angina sufferers.

Many thanks John. I have no better explanation than that the low carb lifestyle has been highly effective for you. I am delighted.

There IS evidence that regularly exercising to your angina threshold does help by encouraging coronary collateral development. However, unlike with calf pain, provoking an unnecessarily severe degree of cardiac ischaemia may be dangerous by causing cardiac rhythm disturbances or possibly initiating a heart attack. So pressing on to maximal tolerable chest pain is not advisable for angina sufferers. Hugh

Hello Hugh,

I was told I had this a couple of years ago. The consultant said exactly what you have written. Thank goodness I am a walker, do yoga and pilates – I can say the condition does improve though I find that if I am tired and do a big walk (6 miles or more) I feel the discomfort more. But it is up to the patient themselves to make the effort – it does pay off!

Thanks Jean and well done – six miles sounds like a long walk with IC. Hugh

Very interesting article. If all goes well I will have a femoral endarterechtomy procedure on 22 April after which I do hope to return for my 2 weekly exercises at the gym.

Thanks Jan. I do hope that the endarterectomy goes well and gets you back to normal. Hugh