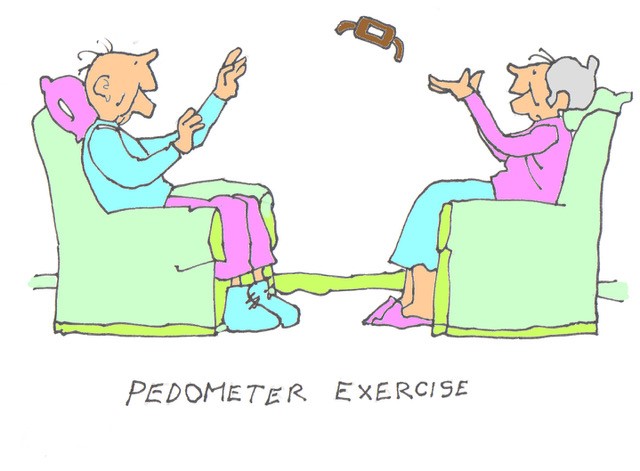

Pedometers

Pedometers are very popular among those wishing to maintain and track their exercise levels. They are used mainly for two purposes:

- Measuring activity (as evidenced by daily steps)

- Motivating increased physical activity

History

In 1965 the Japanese company, Yamasa Tokei, began selling a new step counter called manpo-kei. They promoted its use with a campaign to encourage its use “let’s walk 10,000 steps a day!” This was an entirely arbitrary number but fitted in well for several reasons. First it is a nice round number. Second it is reasonably easily achieved. Rather like the DoH recommendation of 150 minutes of moderate level physical activity per week, it is a level which won’t put people off too much but is certainly enough to be beneficial.

In practice just pottering about as part of a largely sedentary lifestyle will produce a reading of 5,000 or so steps – adding a half hour walk will easily bring it up to around 10,000.

Is 10,000 a reasonable target?

Although the original target of 10,000 is highly arbitrary number, investigations of the effects of different step counts have indicated that it is reasonably valid.

The benefits of different step counts

The biggest relative increase in health benefits of exercise comes from doing nothing to doing something. The more you do the greater the benefits, though the improvement curve flattens out as the daily amount of exercise taken increases. There does not seem to be an upper limit to the exercise level which produces health benefits.

Different benefits require different amounts of exercise. For instance for the obese to lose weight by exercise alone requires much more exercise than demanded by the DoH recommendation – in pedometer terms you need to take more that 20,000 steps daily to lose weight without eating less. There have been a number of studies of the comparative benefits of different step counts. Most have looked at step counts lower than 10,000 and the consistent finding has been that increasing step count, even if well below 10,0000 is associated with a variety of benefits. Here are a few examples:

- A mortality study suggested that increasing numbers of steps were associated with progressive lower all-cause mortality but those who averaged 7,000 to 10,000 steps did just as well as those who walked more than 10,000.

- A controlled study of Type 2 diabetics given an exercise prescription showed that the intervention group increased their daily step count from 5,000 to 6,200 and even this modest increase improved blood sugar control compared to the controls.

- A similar study using a walking programme found a significant reduction of blood pressure in women who increased their count to 9,000 steps.

- A US study of a representative sample US citizens showed a mortality benefit when those taking more that 4,000 steps were compared with those taking fewer than 4,000 steps per day. The benefits plateaued beyond 10,000 steps. A subsequent analysis of the data from this study found that almost as much benefit accrued from performing 8,000 steps for just two days per week.

- A longitudinal study of 5,000 Australian women over seven years found that the risk of developing diabetes was inversely related to the number of daily steps. Each 2,000 steps per day was associated with a 12% fall in incidence of diabetes.

- A meta-analysis of a large number of studies found that the most active quarter had half the mortality rate of the least active quarter.

What about exercise intensity?

The pedometer is a pretty crude way of measuring physical activity (PA) and gives little information about the intensity of that activity. When PA is measured by a rather more sophisticated device, the accelerometer, the intensity is found to be important. Nearly 90,000 individuals without cardiovascular disease were tracked for one week and then followed up for 6.8 years. More daily steps were associated with lower all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease (CVD – ie heart attacks, strokes etc) mortality and cancer mortality. Total PA (equivalent to steps per day) was strongly associated with a decrease in mortality . Vigorous exercise, however, was more effective than moderate intensity PA. Converting a daily 14 minute stroll into a 7 minute brisk walk produced a significantly greater reduction in CVD. Also, purposeful walking – walking to get somewhere rather than just pottering about, seemed to be more beneficial.

And Motivating Increased Activity?

The evidence here is a bit sparse. One study of pedometer tracking to aid the management of obesity showed that wearing a pedometer actually led to less weight loss in the wearers than non-wearers! Combined with a guided weight loss programme, however, wearing an exercise tracker did give better results than the weight loss programme on its own.

In the short term wearing a tracker can certainly improve both PA and physical fitness. A study of their use in a group of inactive adults found that after eight weeks there were increases in activity resulting in an improved cardiorespiratory fitness. Over this short period there were no clinical improvements such as weight loss or lowered blood pressure.

So far these short term increases in PA and CRF have not been found to lead to long-term improvements in health. The best evidence for the overall benefit of wearing such devices comes from a review of five studies which concluded that there is little evidence that activity trackers improve health outcomes.

However, from talking to pedometer users I have little doubt that many of them find them helpful – but it is hard to say that they would do less exercise without their trackers.

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking