How much exercise do we really take?

Illustration

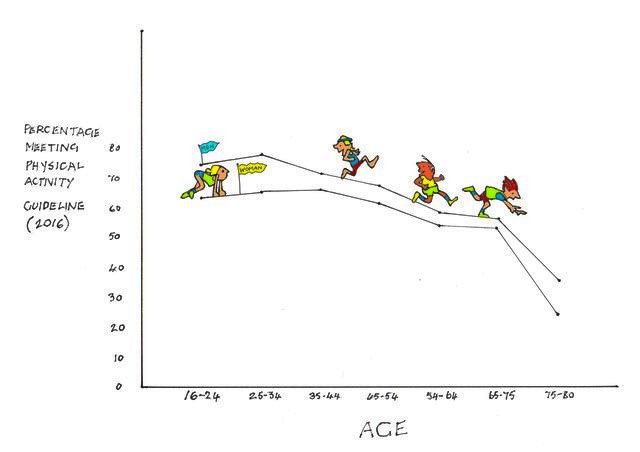

The graph shows the declared level of physical activity as a percentage of the DoH recommended level against increasing age. The downward trend late in life is marked.

Current recommendations

To recap – in 2011 the Department of Health modified its recommendations. It stated ‘Adults should aim to be active daily. Over a week, activity should add up to at least 150 minutes (2½ hours) of moderate-intensity activity in bouts of 10 minutes or more – one way to approach this is to do 30 minutes on at least five days a week. Alternatively, comparable benefits can be achieved through 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity spread across the week or a combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity’, (Department of Health, 2021). The recommendations also added muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days per week that work all major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders and arms).

Social desirability bias

When I was a junior doctor (and long before doctors dared to go on strike) I was taught by a cardiologist how to find out how much any particular patient was smoking.

- Ask the patient how many he/she smokes a day – and double it.

- Ask the spouse how many – and halve it.

- Add the two together and divide by two.

The same formula can be applied to eating – and to taking exercise. The point is that most of are prone to “social desirability bias”. The answers we give to how much we smoke, eat or exercise are probably what we believe but that belief is biased towards what we think would sound best, both to others and to ourselves. On the other hand our spouses tend to take a rather less rosy picture of our habits!

Assessing activity

By questionnaire

Most of the research on the effects of different levels of exercise use questionnaires to assess how much exercise the individuals involve are taking. Unfortunately this is such an inaccurate measure that it has to be taken with a very large pinch of salt.

The inaccuracy of self-reported levels of exercise was shown by a survey performed by the Health Service for England (HSE) in 2008. The HSE performs annual surveys of all sorts of health parameters – BMI, blood pressure, nutrition, housing conditions and so on, tackling different issues from year to year. Quite often physical activity is their subject. Different types of activity are summarised into a frequency–duration scale which takes into account the time spent taking part in physical activities and the number of active days in the last week. By this measure the proportion of adults meeting the recommendation has increased steadily since 1997 for men and 1998 for women. In 1997, 32 per cent of men met the recommendation, increasing to 43 per cent in 2012. Among women, 21 per cent met the recommendation in 1998, increasing to 32 per cent in 2012.

After 2012 the recommendations changed to include shorter bursts of activity, so the figures for the past few years cannot be compared with the earlier figures. Currently the estimates are that 66 per cent of men and 58 per cent of women meet the guidelines. But how accurate are these figures?

The 2008 HSE report found that, based on the participants’ self-reported data, 39 per cent of men and 29 per cent of women in the whole survey met the exercise recommendations of the Chief Medical Officer (CMO). Increasing age and increasing BMI were associated with decreasing levels of activity. At age range 16–24, 52 per cent of men and 35 per cent of women met the recommendations. The numbers fell steadily over the next three decades of life to 41 per cent and 31 per cent. Thereafter the fall was more precipitate, to nine per cent and six per cent for the over-75s.

By measurement

Like other HSE surveys, the report gives a huge amount of additional data, including the effect of obesity and social status on activity and also the different activities included in different age and sex groupings.

In 2008 the survey added a separate assessment of activity levels – it actually measured what people did. The comparison with what they said they did is startling. They used accelerometers to record information on the frequency, intensity and duration of physical activity in one-minute ‘epochs’, showing accurately the actual daily activity of their subjects over a period of one week. Based on the results of the accelerometer study, six per cent of men and four per cent of women achieved the government’s recommended physical activity level, just 15 per cent of the level of compliance indicated by individuals’ own questionnaire responses. Men and women aged 16–34 were most likely to reach the recommended physical activity level (11 per cent and eight per cent respectively), while the proportion of both men and women meeting the recommendations fell in the older age groups. On average, men spent 31 minutes in moderate or vigorous activity (MVPA) in total per day and women an average of 24 minutes. However, most of this was sporadic activity, and only about a third of it was accrued in the bouts of 10 minutes or longer that count towards the government recommendations.

What about physical fitness?

Fitness level is a much better reflection than self-reported activity of how much exercise people actually take. When the effects of physical fitness are compared with stated activity levels, it is physical fitness that is a far better predictor of future heart disease and mortality, particularly in younger subjects.

Next time I will discuss the levels of physical fitness in the population.

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking