Exercise and longevity – Part 1

‘I’m not afraid to die, I just don’t want to be there when it happens.’ Woody Allen

Length of life – lifespan

The bottom line – how long you live. There is no answer to the question ‘What is normal life expectancy?’ but it is certain that our population is nowhere near reaching it. The surprising fact is that, despite our thoroughly unhealthy lifestyles, until very recently we have seen a gradual increase in lifespan. In the years between 1991 and 2014 average life expectancy for men rose from 73.6 years to 79.4. For women the figures were 79.0 rising to 83.1. This unexpected good news has recently hit the buffers, with figures produced by Public Health England suggesting that the trend has now flat-lined. Indeed, the Faculty of Actuaries has calculated that at the age of 65 the life expectancy of a man has fallen by four months and that of a woman has fallen by a whole year – good news for the pensions industry, which will reap a reward of £27 billion in liabilities from company balance sheets. The same is true in the US, where life expectancy fell in 2017 from 78.7 to 78.6, after rising from 69.9 over the previous six decades. More importantly, the duration of healthy life – healthspan – has been falling for several years, while the years spent in poor health has increased. We should not be surprised: just read on.

Effect of exercise on lifespan

There are two ways of judging how much a person exercises:

- Assessing physical activity, either by questionnaire or by direct observation The former is biased by the individual’s tendency to exaggerate, driven by so-called ‘social desirability bias’, and almost always gives a much greater exercise estimate than the latter. Direct observation produces the most accurate measure of physical activity but has a number of problems: it is difficult to do, difficult to compare between exercise types, requires special equipment and is expensive, and it gives a result that applies only to the period of observation. We can all up our game when we know we are being watched.

- Measuring physical fitness There is a direct relationship between amount of exercise taken and physical fitness level, but with wide variations. Other variables also affect the relationship, such as inherited characteristics. However, this method has the strength of producing a measurement that does not depend upon an unreliable witness – the participant.

Exercise volume and longevity

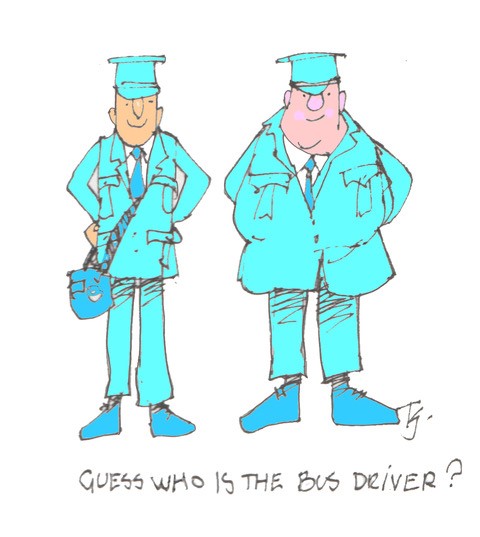

The early observations of the association between amount of exercise taken and longevity involved groups of people who take regular vigorous exercise as part of their daily life, be it either at work or at play. One such was Professor Jerry Morris’s 1950s study looking at the fates of London bus drivers compared with conductors. The model of the driver was sitting for hours behind the wheel, unable to exercise. The conductors, on the other hand, were on their feet all day, moving up and down the stairs and getting plenty of exercise. Sure enough, the drivers had a higher mortality, largely due to a greater risk of coronary disease.

In those days the number of physically active workers was considerably greater than is the case nowadays – mechanisation has greatly reduced the role of jobs in making the working man take exercise. Morris repeated his findings in a comparison of the leisure-time activities of civil servants. Those who exercised vigorously in their spare time fared much better than their sedentary colleagues. A very important finding was the presence of a threshold for the effect of exercise – lower levels of exercise did not prolong life. An approximate level for this threshold was 40 minutes of exercise to a state of breathlessness three to four times per week. Unlike in the bus drive/conductor study, it was only those taking vigorous exercise in their leisure time who benefited.

These findings have been supported by the famous Framingham Study, which followed a large group of middle-aged and older citizens in the US. For this cohort, moderate activity increased the length of life by 1.3 years in men and by 1.5 years in women. High levels of physical activity further increased these figures to 3.7 and 3.5 years respectively.

Sporting activity and longevity

More recent examples of the life-prolonging effect of regular exercise have looked at those who take regular vigorous exercise as part of their sporting activities, such as runners, cyclists and swimmers. One study reviewed 500 runners, aged 50–59, and compared them with age-matched and sex-matched controls. After 19 years, 15 per cent of the runners but 34 per cent of the controls had died. A review of all the available evidence indicates that runners have a 30–50 per cent reduced risk of mortality during follow-up and live approximately 3 years longer than non-runners. Increasing the time spent running and increasing its intensity both produce benefit up to about 4 hours per week and a total dose of 50 MET hours per week. Above this dose of exertion, further benefit is doubtful and there might even be a small reduction of benefit.

A study of 15,000 Olympic medal-winners gives a different perspective, showing a total lifespan about three years longer than that of the general population – irrespective of the colour of the medal! Those involved in aerobic sport had better results than those who took part in power events, and the effect was also enhanced in those who maintained regular exercise after their days of Olympic glory, with an increase in life expectancy of up to five years.

The cynical view

A much-quoted criticism of the benefit of exercise is the cynical suggestion that the amount of time spent exercising is about the same as the increase in lifespan. In this study, such cynicism is convincingly debunked. The authors calculate that every hour spent in exercise increases lifespan by seven hours! Not all studies have agreed on the optimal amount of exercise for prolonging life – some have found a ceiling effect, but the majority have shown a clear association between increasing duration, intensity and frequency of exercise at least up to 300 minutes per week of vigorous exercise.

PS The last word on frailty and provision of care

I received the following comment from my cousin-in-law who lives in Western Australia:

“In my voluntary work, I see this frailty; most places of residential care provide wheeled walking-frames to their residents to reduce their chances of falling. There must be a direct correlation between the use of same and the decline in core strength/stability? Over the years, I’ve seen people shrink – physically and mentally – as their intellectual, social and physical options are limited. There are, however, opportunities here for elderly citizens to stay in their own homes, with government support, because the medical authorities recognise just how good this is for the individual’s health.

Our new government’s election manifesto included care-home workers getting better pay and the installation of a registered nurse on duty 24/7 in every establishment.

Covid has reduced our immigration levels and many care-homes are short-staffed but a pay increase might help recruitment?

An Australian viewpoint (August 2022)”

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking